As a core product of the VRIFY Predict suite for prospectivity mapping, DORA is built to generate exploration targets from multivariate datasets with a level of scale, speed, and complexity unattainable with traditional methods. This primary function sometimes leads to the perception that the software is useful only at major campaign milestones, such as the arrival of new surveys or assay results and the testing of new ideas, but in practice its capabilities extend much further. DORA’s core analytical components, known as Data Augmentation Modules, can operate independently and support interpretation in day-to-day geological analysis.

The following sections highlight three of the many modules currently available in DORA’s expanding Data Augmentation library, illustrating their value in routine geological tasks.

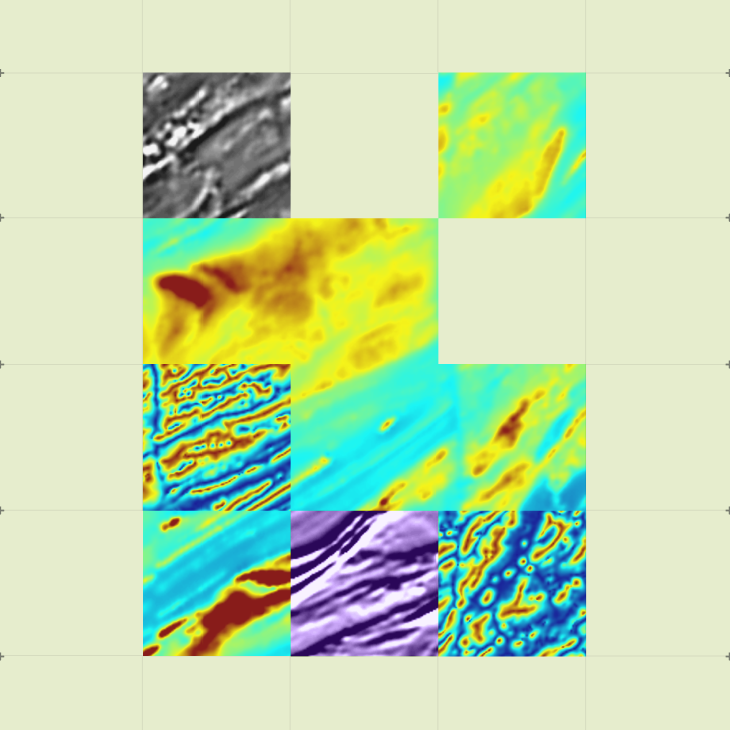

Lineament Maps Module

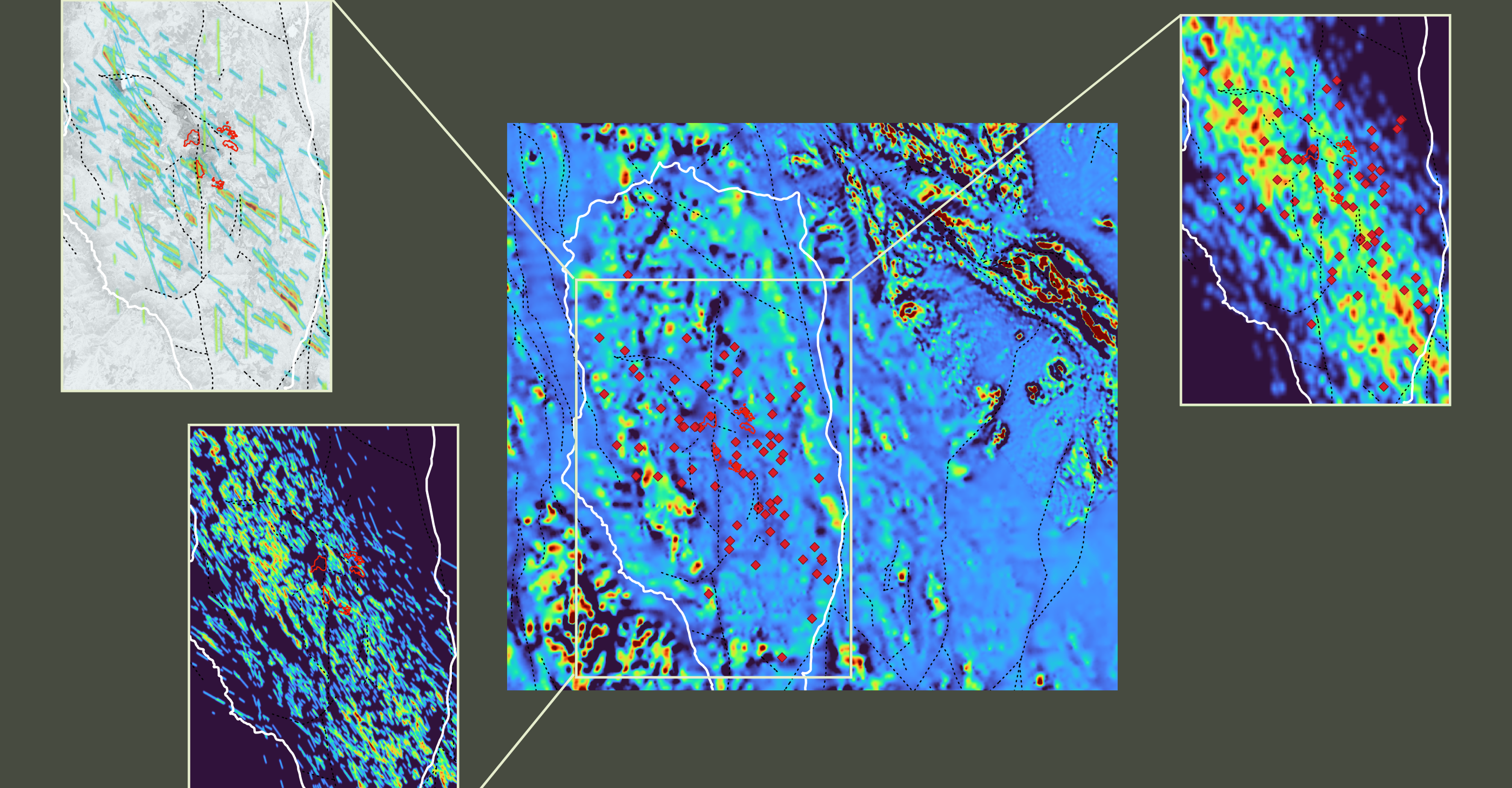

Mapping structures and boundaries, such as faults and lithological contacts, has always been central to exploration, as they are key controls on the localization of mineralization in many mineral systems, from porphyry deposits to orogenic gold. Yet lineaments are still often traced manually from magnetic, gravity, or digital elevation models (DEMs), a labour-intensive effort that can stretch for days and often yields results that vary over time and between interpreters. The Lineament Maps Module automates this step, extracting the same features directly from the grid in minutes and delivering outputs that remain consistent from one run to the next.

At its core, the workflow relies on edge-detection technology. Once identified, the edges are traced into coherent segments and modelled as line features with orientation assigned automatically. The result is a lineament layer grounded directly in the data rather than in hand-drawn interpretation.

Objectivity in analysis drives reproducibility, and together with speed, these define the module’s main advantages. A dataset processed with the same parameters will always return the same baseline, eliminating the variability of manual digitizing and giving geologists a framework they can revisit with confidence. Lineament trends and breaks can be evaluated against geochemical patterns without shifting baselines. At the regional scale, the reproducible lineament layers provide a solid basis for extending interpretations across project boundaries with the support of public survey data.

From the same processing run, the Lineament Maps Module outputs two derivative layers that deepen structural assessment: lineament density and complexity.

- Lineament density measures how closely lineaments and potential structures are spaced. Concentrated areas often reflect repeated fracturing, a condition that sustains permeability and increases the likelihood of fluid flow. Because lineaments frequently coincide with lithological contacts or faults, density maps can also highlight features that exert strong control on mineralization across a range of deposit types.

- Lineament complexity captures another dimension of potential structural influence. Expressed as a heat map, it shows where lineaments converge and overlap or shift orientation, potentially demarcating fluid pathways that may have focused or trapped mineralization. By quantifying the intensity of these interactions, the complexity layer replaces a qualitative judgement with a reproducible map that can inform structural interpretations or feed directly into prospectivity models.

Together, these two products leverage the value of the input layer, whether geophysical surveys, DEMs, or Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), and therefore inherit its objectivity.

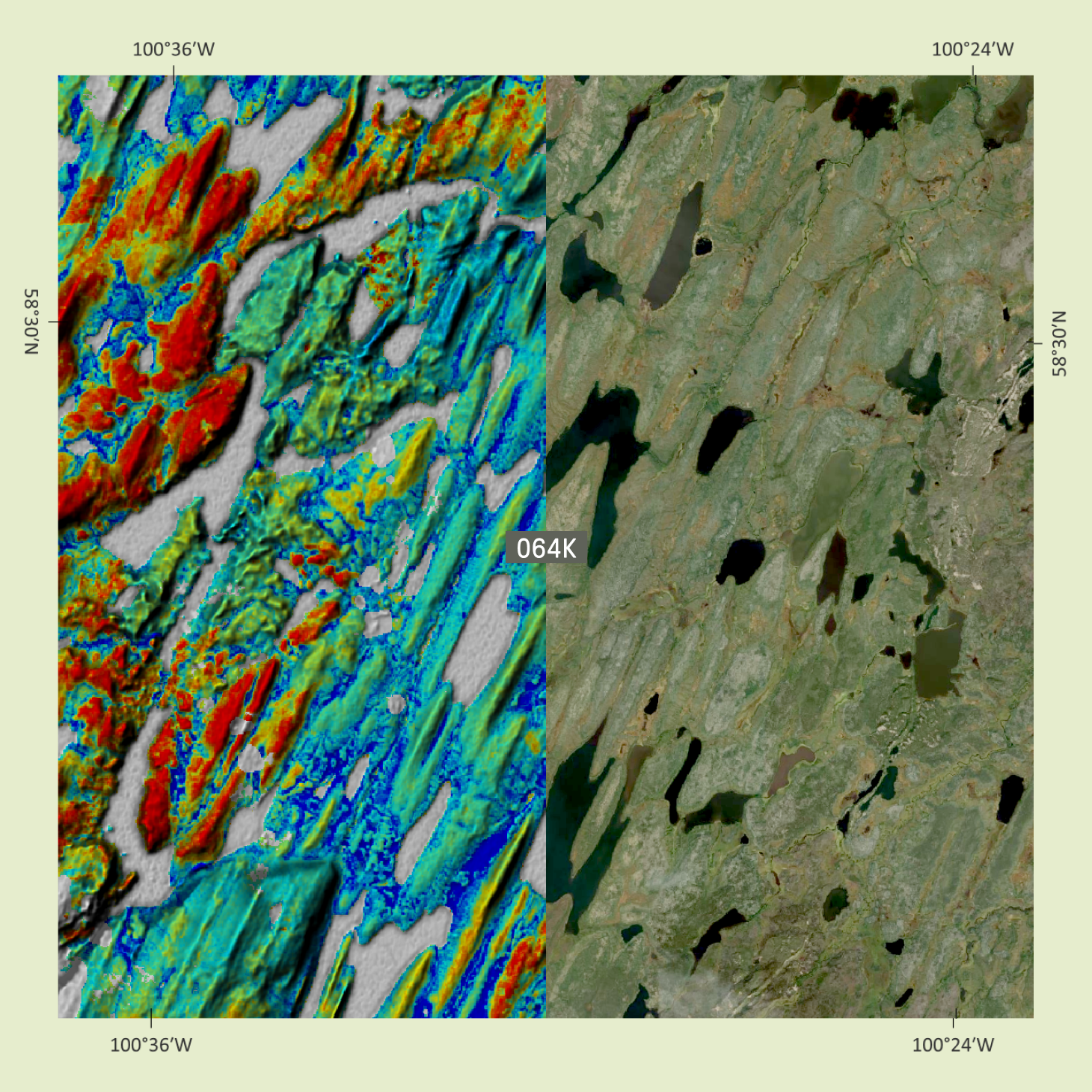

Distance Maps Module

While structural patterns are essential, proximity to key geological features also guides many exploration decisions. Geologists routinely assess distances to faults, stratigraphic contacts, intrusions, conductors, and other elements that often influence where mineralization is focused. In conventional GIS workflows, building distance maps requires repeated manual steps that slow the process.

The Distance Maps Module offers a more consistent and efficient approach. Within DORA, it quantifies and rasterizes spatial relationships to produce geologically grounded exploration targets. Used independently, it enables geologists to compute distances from vector inputs, whether polyline features by attributes such as shear zones and lithological boundaries, or specific lithological polygons favourable for mineralization.

Functionally, the module calculates Euclidean distance, a straight-line measure from each grid cell to the nearest selected feature. The results appear as heat maps where, for example, warmer colours mark greater proximity to the inputs and cooler tones represent increasing distance from them. Treating all features consistently allows the data to reveal which spatial associations with mineralization are most significant.

This capability is particularly valuable for structurally controlled deposits, such as orogenic gold, where mineralization tends to cluster along major deformation corridors and may be further localized by cross-cutting or subsidiary structures. The Distance Maps Module provides a consistent baseline for geologists to identify which of these features exert the strongest control. The same logic extends to point data, where proximity to mapped alteration or electro-magnetic conductor picks may highlight or vector to mineralization.

Data Density Module

Exploration datasets are rarely uniform. Some regions contain dense data clusters, while others remain sparsely and heterogeneously covered or entirely untested, particularly with respect to geochemistry and ground geophysics. Mapping this variation helps assess confidence in data-supported prospectivity and gauge how thoroughly a property or district has been explored. Yet assembling this perspective manually across datasets in GIS is often time-consuming and inconsistent, depending on how information is displayed or weighted.

The Data Density Module is DORA’s core component responsible for measuring the spatial distribution of all data to support AI-assisted target generation. As a standalone tool, it produces a continuous representation — by type if desired — of coverage within minutes, revealing variations in sampling and survey coverage while highlighting where exploration activities have been focused and which areas are underexplored.

The module integrates diverse geoscientific inputs, including outcrop data and structural measurements, geochemical analyses, drillhole traces, and geophysical surveys, into a single analytical layer. Each grid cell is assigned a value representing the count of nearby data points, producing a grid that grades from data-rich areas to areas with limited information.

This approach provides a quantitative framework for evaluating data coverage and prioritizing follow-up work. Areas of low data density are not necessarily without potential; they are simply less data-constrained, a distinction that helps avoid false confidence in poorly informed domains. Visualizing these spaces encourages more objective, data-driven planning and helps reduce bias toward historically well-sampled zones.

.png)

Although the Lineament Maps, Distance Maps, and Data Density Modules address different aspects of geological work, they operate according to the principles shared across the broader Data Augmentation library in DORA. Parameters can be tuned to the scale of interest — from regional frameworks to detailed project studies — while outputs update when new information arrives, allowing interpretations to advance without reconstructing earlier steps.

By replacing what would, in many cases, require a sequence of GIS operations with a single workflow, these modules generate consistent results and reduce the variability that often appears when grids are rebuilt in different environments. As standalone tools, they provide a reliable analytical foundation that supports the day-to-day technical work underlying exploration programs.

If you want to learn more about DORA and its full set of Data Augmentation Modules, book a demo with our Geoscience Team.

<hr/>

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)